Art History Professor Tracks ‘Missing Pages’ from 13th-Century Armenia

By Jeffrey Day | Originally published at UC Davis College of Letters and Science

UC Davis art history professor Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh’s The Missing Pages: The Modern Life of a Medieval Manuscript from Genocide to Justice starts, figuratively and literally, on June 1, 2010, in Los Angeles Superior Court. That day, the J. Paul Getty Museum was sued for the return of eight illustrated pages from a 13th-century Armenian book of gospels.

The Missing Pages, just published by Stanford University Press, took Watenpaugh to the places the pages had traveled, from their creation in 1256 in present-day Turkey, to Armenia, Syria, Ellis Island, Massachusetts and Los Angeles. The illustrated pages disappeared during the Armenian genocide of the early 20th century and were purchased by the museum in 1994.

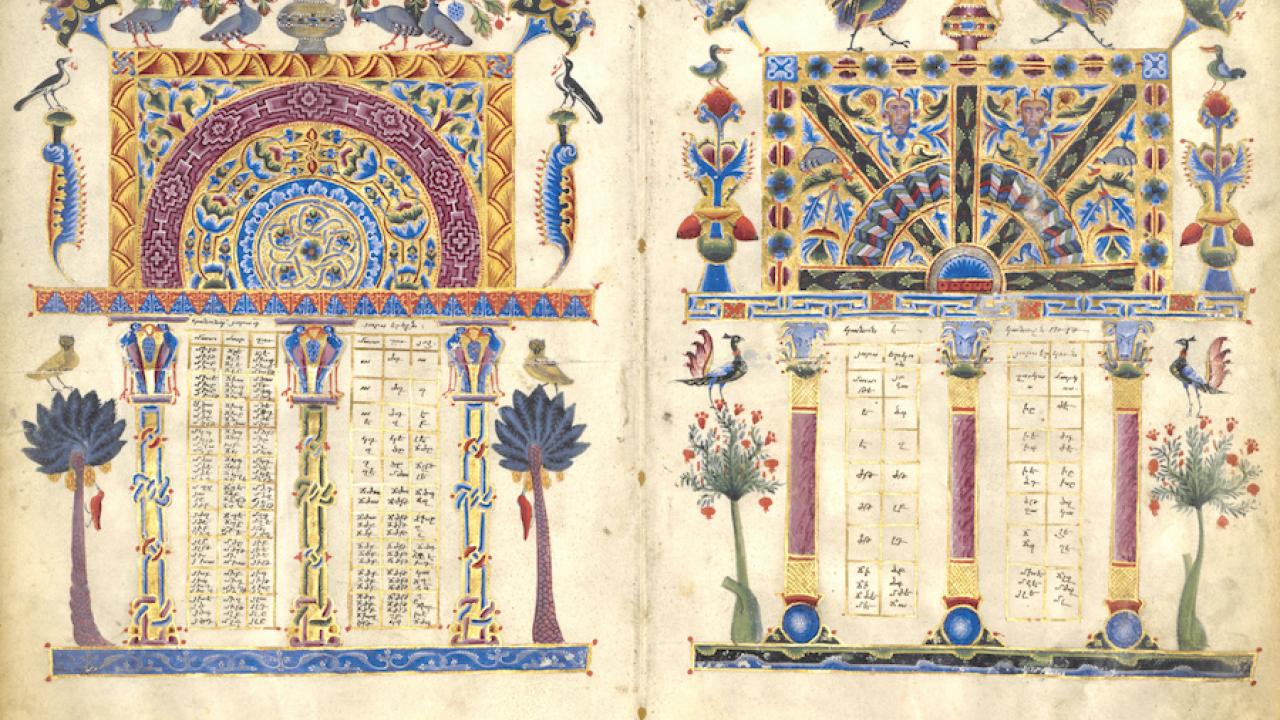

The pages, removed from the Zeytun Gospels, are brilliantly illustrated with ornate columns, birds, trees and flowers painted in blue, red, lavender and gold by Toros Roslin, a groundbreaking Armenian manuscript illustrator whose abstract designs and naturalistic elements were unique. The Gospels are evangelists’ account of Christ’s life; the missing pages are the canon tables, a guide to the Gospels.

More than art

The pages are great works of art, but there was a much bigger story Watenpaugh wanted to tell. Her book is just as much about the people and places impacted by the genocide in which an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were killed by the Turkish Ottoman government. The mass killings, forced marches and exile starting in 1915 led to the diaspora of the Armenian people around the globe. That included the family that brought the pages to the United States, as well as Watenpaugh’s grandparents who settled in Egypt and Lebanon, where she was born.

“It’s the story of the pages, but also the story of people who had come in contact with them and how that affected and changed them,” Watenpaugh said. “The biggest discovery for me was how many people tried to save art during this cataclysmic time, how they latched onto special objects and kept them through multiple migrations. It showed me how central art is to resilience.”

Exploring new territory

When Watenpaugh heard about the lawsuit filed by Western Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America, she wanted to be part of the discussion.

“It resonated with me in many ways,” she said. “I’m an art historian, I had been a Getty Fellow, and the Armenian Genocide is part of my history.”

Within a month of the suit being filed, she submitted an op-ed to The Los Angeles Times. Not only did they publish it, the editor encouraged her to “tell the story.” After initial research, Watenpaugh met with Stanford University Press Editor-in-Chief Kate Wahl, and both felt The Missing Pages would be a story with broad appeal, an exciting and moving journey through the history of the pages, people and places.

“We both agreed we wanted to do a book that would reach a wide audience, but it was daunting,” Watenpaugh said. “I had to learn to write in a completely new way. It took a long time to find the right voice.”

Retracing the 800-year journey

Watenpaugh is primarily a scholar of urban and architectural history of the Middle East from the 16th century forward, although she has written extensively about a wide range of Middle Eastern architecture, art and cultural heritage and its destruction. She has been a faculty member of the Department of Art and Art History in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science since 2006.

“Illustrated manuscripts from the 13th century were not my medium or my time period,” she said. “It was a stretch, but I felt the story needed to be told.”

Watenpaugh retraced the pages’ journey, using her architectural history expertise to draw detailed descriptions of how the places looked when the pages were there and what they are like now. She constantly came across reminders of the genocide that sent the pages around the globe.

“That helped me tell the story,” she said. “It’s the way my mind works and the way I can organize things.”

The Zetyun Gospels were created in Hromkla, a religious center in what is now southern Turkey. By the 17th century, the manuscript had moved about 125 miles away to Zeytun, the place that gave the volume its name. It remained there for 300 years, under lock and key, accessible to only a chosen few. At the start of the genocide it was conveyed to Marash, a nearby city that was a haven for refugees. Then the book rapidly and repeatedly changed hands and may have even been lost in the snow for a short while.

“I was still able to expand the story and capture some of the human dimension,” Watenpaugh said. “I was amazed I was able to find anything.” Still, as she writes in the book, “the events that took place from this point onward have disappeared into the fog of time.”

What is known: the book came into the possession of the Atamian family and someone in the family removed the illustrated pages.

Coming to America

The Atamians ended up in Aleppo, Syria, the jumping-off point for fleeing Armenians. On July 6, 1923, the family — Melkon, a dentist, Mariam, and five of their children — arrived at Ellis Island, New York, apparently carrying the pages. They settled in Newton, Massachusetts.

For the next 60 years the pages remained with the family, but were rarely talked about in specific terms or looked at. Around 1980, they were passed on to Gil Atamian, grandnephew of Melkon. In 1990, Gil showed them to Armenian Apostolic Church officials who brought them to the attention of an art historian. They were identified as the missing pages from the Zeytun Gospels and also attributed to Toros Roslin, as his earliest signed works.

With that, those eight pages went from being mysterious family heirlooms to artistic and religious treasures worthy of serious study and inclusion in major museum collections. They also became worth a lot of money.

In 1994, one of the pages went on display in “Treasures of Heaven: Armenian Illuminated Manuscripts” at the Morgan Library in New York. A few months later, the Getty quietly purchased the purloined pages from Gil Atamian, reportedly for about $1 million.

Listen to Watenpaugh read from her book

A story without an end

When Watenpaugh started her research for the book, she didn’t know how the story would end. That would have to wait for the 21st-century U.S. justice system.

The story came to its conclusion in a faster and simpler way than expected, given the long and complicated history of the pages. In 2015, the Getty acknowledged the Armenian Church’s historical ownership of the pages and the church donated the pages to the Getty Museum. The museum changed the provenance citation of the pages to “gift of The Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia, by agreement.”

Not everyone was happy, saying the pages should be reunited with the Zeytun Gospels that are in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts. Overall the settlement received remarkably little attention. With 2015 being the 100th anniversary of the genocide, other Armenia-related commemorations may have pushed it off the front page, Watenpaugh said.

For Watenpaugh, the ending was fine for her as an art historian, as the author of a book about the missing pages, and as an Armenian. It was a solution not very different than what she had suggested in her op-ed in 2010. The ownership is acknowledged, the pages are preserved, and they are at times available to the public to view in Los Angeles, where as many as 500,000 people of Armenian extraction live.

“Both sides made concessions, and both sides achieved some of their original goals,” she said. “For the Zeytun Gospels, there could not be a return to the past, and the injuries of war and genocide can never be repaired. The greatest impact of settlements like this is that they look forward, to greater collaboration between museums and communities over the appreciation of works of art and the telling of difficult histories.”